Millman’s Theorem

Set of parallel-connected branches

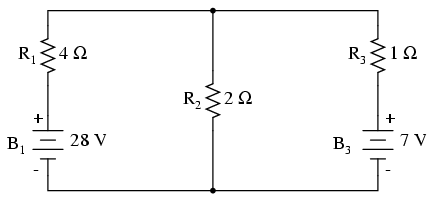

In Millman’s Theorem, the circuit is re-drawn as a parallel network of

branches, each branch containing a resistor or series battery/resistor

combination. Millman’s Theorem is applicable only to those circuits

which can be re-drawn accordingly. Here again is our example circuit

used for the last two analysis methods:

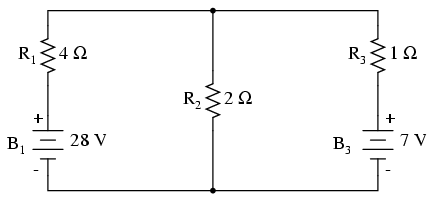

And here is that same circuit, re-drawn for the sake of applying Millman’s Theorem:

By considering the supply voltage within each branch and the resistance

within each branch, Millman’s Theorem will tell us the voltage across

all branches. Please note that I’ve labeled the battery in the rightmost

branch as “B3” to clearly denote it as being in the third branch, even though there is no “B2” in the circuit!

Millman’s Theorem is nothing more than a long equation, applied to any

circuit drawn as a set of parallel-connected branches, each branch with

its own voltage source and series resistance:

Substituting actual voltage and resistance figures from our example

circuit for the variable terms of this equation, we get the following

expression:

The final answer of 8 volts is the voltage seen across all parallel branches, like this:

The polarity of all voltages in Millman’s Theorem are referenced to the

same point. In the example circuit above, I used the bottom wire of the

parallel circuit as my reference point, and so the voltages within each

branch (28 for the R1 branch, 0 for the R2 branch, and 7 for the R3 branch)

were inserted into the equation as positive numbers. Likewise, when the

answer came out to 8 volts (positive), this meant that the top wire of

the circuit was positive with respect to the bottom wire (the original

point of reference). If both batteries had been connected backwards

(negative ends up and positive ends down), the voltage for branch 1

would have been entered into the equation as a -28 volts, the voltage

for branch 3 as -7 volts, and the resulting answer of -8 volts would

have told us that the top wire was negative with respect to the bottom

wire (our initial point of reference).

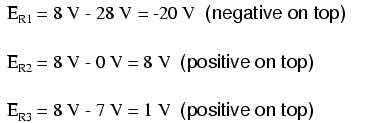

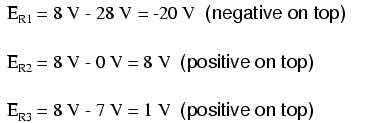

To solve for resistor voltage drops, the Millman voltage (across the

parallel network) must be compared against the voltage source within

each branch, using the principle of voltages adding in series to

determine the magnitude and polarity of voltage across each resistor:

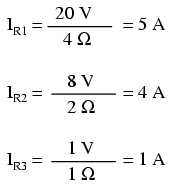

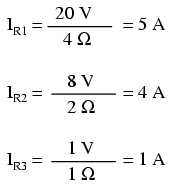

To solve for branch currents, each resistor voltage drop can be divided by its respective resistance (I=E/R):

The direction of current through each resistor is determined by the polarity across each resistor, not by the polarity across each battery, as current can be forced backwards through a battery, as is the case with B3 in

the example circuit. This is important to keep in mind, since Millman’s

Theorem doesn’t provide as direct an indication of “wrong” current

direction as does the Branch Current or Mesh Current methods. You must

pay close attention to the polarities of resistor voltage drops as given

by Kirchhoff’s Voltage Law, determining direction of currents from

that.

Millman’s

Theorem is very convenient for determining the voltage across a set of

parallel branches, where there are enough voltage sources present to

preclude solution via regular series-parallel reduction method. It also

is easy in the sense that it doesn’t require the use of simultaneous

equations. However, it is limited in that it only applied to circuits

which can be re-drawn to fit this form. It cannot be used, for example,

to solve an unbalanced bridge circuit. And, even in cases where

Millman’s Theorem can be applied, the solution of individual resistor

voltage drops can be a bit daunting to some, the Millman’s Theorem

equation only providing a single figure for branch voltage.

As

you will see, each network analysis method has its own advantages and

disadvantages. Each method is a tool, and there is no tool that is

perfect for all jobs. The skilled technician, however, carries these

methods in his or her mind like a mechanic carries a set of tools in his

or her tool box. The more tools you have equipped yourself with, the

better prepared you will be for any eventuality.

Set of parallel-connected branches

In Millman’s Theorem, the circuit is re-drawn as a parallel network of

branches, each branch containing a resistor or series battery/resistor

combination. Millman’s Theorem is applicable only to those circuits

which can be re-drawn accordingly. Here again is our example circuit

used for the last two analysis methods:

And here is that same circuit, re-drawn for the sake of applying Millman’s Theorem:

By considering the supply voltage within each branch and the resistance

within each branch, Millman’s Theorem will tell us the voltage across

all branches. Please note that I’ve labeled the battery in the rightmost

branch as “B3” to clearly denote it as being in the third branch, even though there is no “B2” in the circuit!

Millman’s Theorem is nothing more than a long equation, applied to any

circuit drawn as a set of parallel-connected branches, each branch with

its own voltage source and series resistance:

Substituting actual voltage and resistance figures from our example

circuit for the variable terms of this equation, we get the following

expression:

The final answer of 8 volts is the voltage seen across all parallel branches, like this:

The polarity of all voltages in Millman’s Theorem are referenced to the

same point. In the example circuit above, I used the bottom wire of the

parallel circuit as my reference point, and so the voltages within each

branch (28 for the R1 branch, 0 for the R2 branch, and 7 for the R3 branch)

were inserted into the equation as positive numbers. Likewise, when the

answer came out to 8 volts (positive), this meant that the top wire of

the circuit was positive with respect to the bottom wire (the original

point of reference). If both batteries had been connected backwards

(negative ends up and positive ends down), the voltage for branch 1

would have been entered into the equation as a -28 volts, the voltage

for branch 3 as -7 volts, and the resulting answer of -8 volts would

have told us that the top wire was negative with respect to the bottom

wire (our initial point of reference).

To solve for resistor voltage drops, the Millman voltage (across the

parallel network) must be compared against the voltage source within

each branch, using the principle of voltages adding in series to

determine the magnitude and polarity of voltage across each resistor:

To solve for branch currents, each resistor voltage drop can be divided by its respective resistance (I=E/R):

The direction of current through each resistor is determined by the polarity across each resistor, not by the polarity across each battery, as current can be forced backwards through a battery, as is the case with B3 in

the example circuit. This is important to keep in mind, since Millman’s

Theorem doesn’t provide as direct an indication of “wrong” current

direction as does the Branch Current or Mesh Current methods. You must

pay close attention to the polarities of resistor voltage drops as given

by Kirchhoff’s Voltage Law, determining direction of currents from

that.

Millman’s

Theorem is very convenient for determining the voltage across a set of

parallel branches, where there are enough voltage sources present to

preclude solution via regular series-parallel reduction method. It also

is easy in the sense that it doesn’t require the use of simultaneous

equations. However, it is limited in that it only applied to circuits

which can be re-drawn to fit this form. It cannot be used, for example,

to solve an unbalanced bridge circuit. And, even in cases where

Millman’s Theorem can be applied, the solution of individual resistor

voltage drops can be a bit daunting to some, the Millman’s Theorem

equation only providing a single figure for branch voltage.

As

you will see, each network analysis method has its own advantages and

disadvantages. Each method is a tool, and there is no tool that is

perfect for all jobs. The skilled technician, however, carries these

methods in his or her mind like a mechanic carries a set of tools in his

or her tool box. The more tools you have equipped yourself with, the

better prepared you will be for any eventuality.

No comments